I have always felt Russian literature melancholic and gloomy. White Nights was the first piece I read and I still remember a distinct sadness growing as the story unfolded. Today, although I love every bit of Chekhov’s rich and powerful short stories, I can only take one at a time. Have I always stumbled upon the most disheartening stories? I recently discovered an interesting way to test it, Matthew Jockers’ syuzhet package for R, which allows you to extract sentiment from a text.

My nights came to an end with a morning. The weather was dreadful. It was pouring, and the rain kept beating dismally against my windowpanes

Fyodor Dostoyevsky - White nights

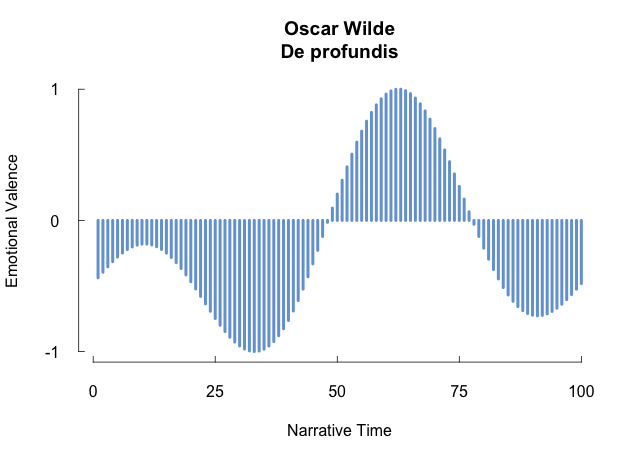

The package provides several tools. One is to display the emotional valence of a text in the y axis, scaled to fit the range 1 to -1, or positive to negative respectively, along the narration time in percentage points, which are displayed in the x axis. As an example, you can see below the plot corresponding to Wilde’s De profundis. The letter shows a negative emotional valence all through the first half, rising to a positive one right until one fourth of the letter is left, where it falls again.

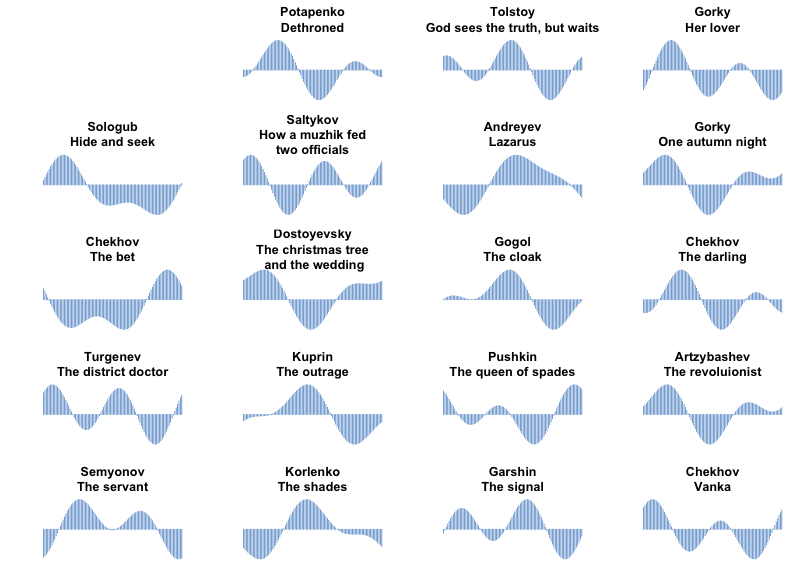

To test my idea, namely Russian literature tendency towards negativity, I selected a small sample of nineteen short stories written by some of the most important authors of the 19th century, which is conveniently collected in the free and publicly available selection Best Russian Short Stories.

The results of this very small sample show that there is no clear trend in them towards negative emotional valence. Although there are indeed ups and downs, nine of these stories, roughly half of them, reach their denouement on a positive note. Therefore, suggesting that I have been rather unlucky when choosing what to read.

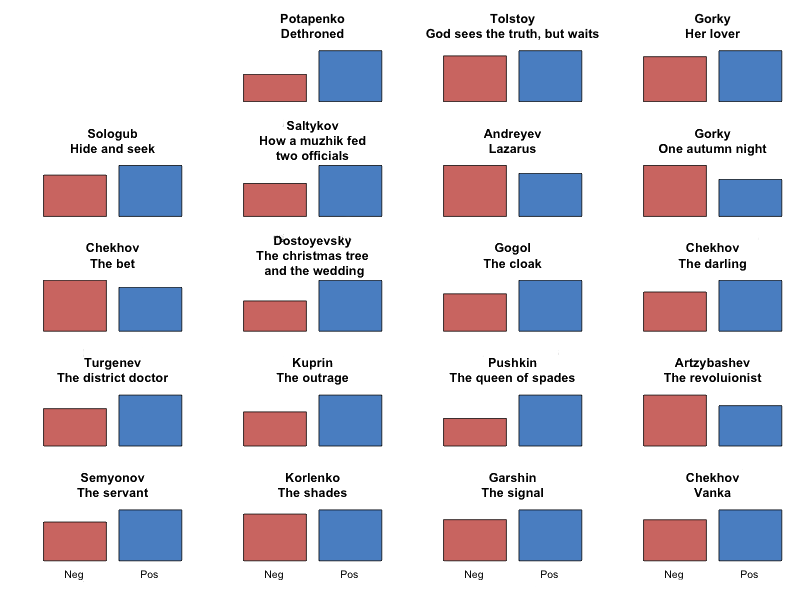

Alternatively, the syuzhet package allows to extract the two major emotions - negative and positive - in a given text, which I have plotted below in red and blue respectively. Once more, no specific trend towards negative values seems to appear.

Life is a vexatious trap; when a thinking man reaches maturity and attains to full consciousness he cannot help feeling that he is in a trap from which there is no escape

Anton Chekhov - Ward No.6

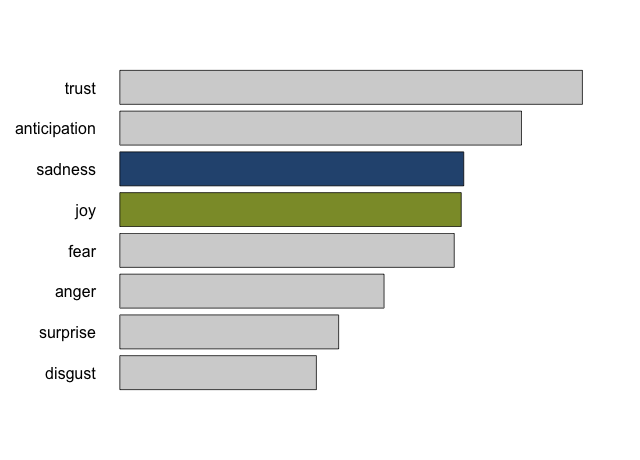

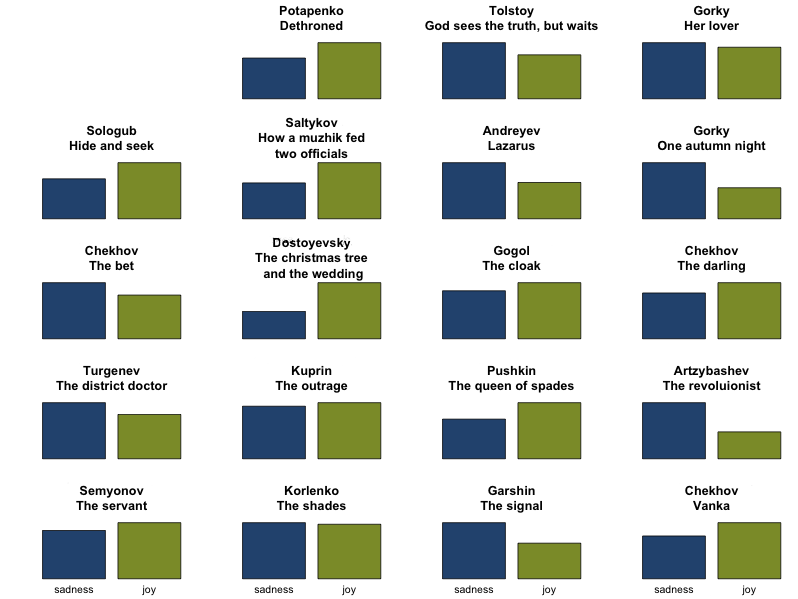

This type of analysis can go deeper to examine other eight major emotions. The result is that for the nineteen stories as a whole the dominant emotions seem to be trust and anticipation, and right after them come sadness and joy; just slightly more sadness than joy.

Once again, although there are some rather sad stories like The revolutionist or The signal, there does not seem to be any clear propensity for sadness.

In summary, according to this - arguably rather small sample - there does not seem to be any indication to sustain my belief that Russian literature is especially sad or melancholic. However, there are limitations to this analysis, which will appear obvious to anyone who has read any of the stories selected.

Chekhov’s Vanka - according to this analysis - appears to end on a positive note, to be overall more positive than negative, and to contain more joy than sadness. However, you might feel otherwise after reading it. Natural Language Processing provides increasingly powerful tools but there are still subtleties and connotations embedded in literature and language that it cannot grasp and that one can appreciate - and definitely enjoy - fully by reading.

* Eileen Clancy has put together a comprehensive storyline of the attention and critique received by the syuzhet package since it came out in February 2015

Find the R code on GitHub.